Trends in the Piedmont - Ned Goodwin MW

Master of Wine Ned Goodwin visited Vinitaly 2022 for Langton’s and shares his insights around trends in Piedmont. Ned looks at Barolo, site selection, the rise of Barbaresco, the fashionability of the Alto Piedmont, the dabble with wholebunch, infusion versus extraction, earlier pruning and the latest bandwagon.

I travelled to Vinitaly, the world’s largest wine fair. It is held in Verona, a picturesque town in the heart of the Veneto. Verona is as famous as the fantastical setting for Romeo and Juliet, as it is for Valpolicella and Amarone, made in the nearby hills.

With more than 4,000 exhibitors, quintuple that number of wines and over 30,000 international buyers, the fair facilitated a giddy sense of liberation, as much from the pandemic as from our inability to socialise, network and conduct business over a glass of wine over the past few years. Vinitaly was a symbol of the wine world’s restoration to a functional axis, a liminal sense of earnestness meshed with a visceral desire to let loose.

Michele Chiaro Piedmont

Indeed, respective trends may have been palpable in the Halls of Industry that make up the fair, yet the maskless throngs that crowded Bottega del Vino each night, Verona’s famous enoteca, were hellbent on digesting as much Franciacorta and Champagne as possible before stumbling to the next agora. Once business was done at the fair, the nights were for revelry, resplendent with live music and assorted cultural activities designed by Vinitaly’s organisers.

‘...the new Burgundy.’

It is no hyperbole to state that Piedmont and, more specifically, the Langhe, will soon be the new Burgundy. If the Liv-ex Fine Wine Index is anything to go by, perhaps it already is. Its most lauded wines, Barolo and Barbaresco, are firmly entrenched in the pantheon of the superlative. Yet as Global Warming’s encroachment threatens established wine cultures from varietal makeup, farming practices and site selection, it is clear that the Piedmontese are making changes to obviate these threats, while schisms in traditional perceptions are becoming increasingly apparent.

Let’s discuss some of these, as evident as any Vinitaly as they were during my visit to the Langhe after the fair.

Site Selection

Cooler sites, once disregarded or perceived as second tier, are now prime real estate. Barolo crus including Ravera in Novello, Monvigliero in Verduno and Gabutti in Serralunga are, in better hands, among the highest performing of all Baroli despite their elevated, exposed and cooler meso-climates. The qualitative hegemony of established crus, none more famous than Cannubi, is being challenged. During one of my tastings, a famous winemaker posited that ‘Cannubi seldom moves (me) any more.’ This vast amphitheatre, Barolo’s largest cru, is hot and sandy. Sand is free-draining with little capacity to absorb and retain water, auguring poorly in the face of Climate Change. This train of thought could be extended, perhaps, to suggest the brighter future of the heavier Serravalian soils of Monforte and Serralunga as opposed to the lighter, sand-infused turf of la Morra, sections of Castiglione di Falletto and the commune of Barolo itself.

The Rise of Barbaresco

Noteworthy, too, is the stellar performance of Barbaresco over recent vintages, particularly the hot 2017 and forward, more approachable 2018s. It is suggested that the more nutrient-rich soils of Barbaresco, coupled with the cooling proximity of the Tanaro River, serve to attenuate the ripening season while suffusing the grapes with physiologically ripe, long-chained tannins. This was no mean feat in 2018 when many wines, despite their flirtatious fruit, were bedevilled by a gritty, underripe astringency.

Noteworthy, too, is the stellar performance of Barbaresco over recent vintages, particularly the hot 2017 and forward, more approachable 2018s. It is suggested that the more nutrient-rich soils of Barbaresco, coupled with the cooling proximity of the Tanaro River, serve to attenuate the ripening season while suffusing the grapes with physiologically ripe, long-chained tannins. This was no mean feat in 2018 when many wines, despite their flirtatious fruit, were bedevilled by a gritty, underripe astringency.

Elisa Scavino of Paolo Scavino with Ned Goodwin MW at Vinitaly22

The Fashionability of the Alto Piedmont

It is no surprise that the Alto Piedmont, abutting the border of Lombardy and Lake Maggiore north of Torino, is conveniently serviced by its cooler climatic mantle. It is indisputably Piedmont’s hippest sub-region, emphasised by the recent purchase of the Nervi estate by Roberto Conterno of Giacomo Conterno, arguably Barolo’s greatest producer. It was my 10th Vinitaly, yet the first time I witnessed an entire stand dedicated to wines from these parts: Ghemme, Gattinara and Boca. Here, Nebbiolo is known as Spanna and is frequently blended with Vespaiola and Uva Rara, varieties as synergistic with Oltrepo Pavese and Buttafuoco further north. The wines are pinot-esque to draw on the cliched comparison of Pinot Noir with Nebbiolo, thrumming with a red-fruited vitality, bright acidity and firm tannins, considerably softer than Barolo or Barbaresco, but assertive all the same.

It is no surprise that the Alto Piedmont, abutting the border of Lombardy and Lake Maggiore north of Torino, is conveniently serviced by its cooler climatic mantle. It is indisputably Piedmont’s hippest sub-region, emphasised by the recent purchase of the Nervi estate by Roberto Conterno of Giacomo Conterno, arguably Barolo’s greatest producer. It was my 10th Vinitaly, yet the first time I witnessed an entire stand dedicated to wines from these parts: Ghemme, Gattinara and Boca. Here, Nebbiolo is known as Spanna and is frequently blended with Vespaiola and Uva Rara, varieties as synergistic with Oltrepo Pavese and Buttafuoco further north. The wines are pinot-esque to draw on the cliched comparison of Pinot Noir with Nebbiolo, thrumming with a red-fruited vitality, bright acidity and firm tannins, considerably softer than Barolo or Barbaresco, but assertive all the same.

The Dabble with Whole Bunch

As a Master of Wine student, it was sacrilege to consider the use of whole bunches with a grape variety as inherently tannic as Nebbiolo. Perceptions have clearly changed over the last decade because at least half of all producers I visited in the Piedmont were dabbling with wholebunch. Some may laugh it off as a trend, yet in lieu of Global Warming the addition of stems to the ferment achieves a number of things beyond imparting spicy complexity and additional tannic mettle. Advantageously, the ripening seasons in the Piedmont are generally long enough to lignify grape stems, turning them brown, chewy and sweet. Adding them to the ferment lightens colour and lowers acidity due to their potassium content. A stylistic risk, perhaps. Yet the brittle tannins inherent to shorter and warmer growing seasons can be shaped and sculpted with their addition in regions such as this, with attenuated growing seasons. In essence, the douse of polyphenols they provide meshes with tannins from the grape skins and the oak to polymerise into long-chained, more supple tannins. These imbue poise and grace to the ensuing wines, obviating the brusque, thick-skin tannins that are more prevalent in the hotter seasons that are becoming the norm.

As a Master of Wine student, it was sacrilege to consider the use of whole bunches with a grape variety as inherently tannic as Nebbiolo. Perceptions have clearly changed over the last decade because at least half of all producers I visited in the Piedmont were dabbling with wholebunch. Some may laugh it off as a trend, yet in lieu of Global Warming the addition of stems to the ferment achieves a number of things beyond imparting spicy complexity and additional tannic mettle. Advantageously, the ripening seasons in the Piedmont are generally long enough to lignify grape stems, turning them brown, chewy and sweet. Adding them to the ferment lightens colour and lowers acidity due to their potassium content. A stylistic risk, perhaps. Yet the brittle tannins inherent to shorter and warmer growing seasons can be shaped and sculpted with their addition in regions such as this, with attenuated growing seasons. In essence, the douse of polyphenols they provide meshes with tannins from the grape skins and the oak to polymerise into long-chained, more supple tannins. These imbue poise and grace to the ensuing wines, obviating the brusque, thick-skin tannins that are more prevalent in the hotter seasons that are becoming the norm.

Infusion Over Extraction

No matter where I went, makers were speaking of longer, gentler macerations of the red grape skins with the must. Many have substituted the term ‘extraction’ with the more fashionable ‘infusion’, implying as much. In other words, as growing seasons become shorter and hotter, grape skins become thicker to promote survival and the propagation of the species. This means burlier, less refined tannins. To tone them, longer extractions without the traditional agitation of punch-downs or pump-overs, are becoming increasingly de rigueur. Open-topped fermenters with partly submerged head-boards to keep the cap moist and in some instances, ceramic and terracotta eggs, are the vessels of choice. The bi-product of fermentation, CO2, keeps the ferment moving without any interference. Some producers continue to champion roto-fermenters, too, albeit, programmed to the lowest speed. This way, the solids to juice ratio can be controlled and ‘infused’ according to the material on hand. Cavalotto, irrefutably among the top five regional producers and responsible for the best wines that I tasted during the trip, is one such practitioner. Oak, too, is shifting. Barriques are largely a thing of the past, while the prevalence of traditional Slavonian botti is being challenged by the uptempo pervasiveness of Stockinger oak, from Austria.

No matter where I went, makers were speaking of longer, gentler macerations of the red grape skins with the must. Many have substituted the term ‘extraction’ with the more fashionable ‘infusion’, implying as much. In other words, as growing seasons become shorter and hotter, grape skins become thicker to promote survival and the propagation of the species. This means burlier, less refined tannins. To tone them, longer extractions without the traditional agitation of punch-downs or pump-overs, are becoming increasingly de rigueur. Open-topped fermenters with partly submerged head-boards to keep the cap moist and in some instances, ceramic and terracotta eggs, are the vessels of choice. The bi-product of fermentation, CO2, keeps the ferment moving without any interference. Some producers continue to champion roto-fermenters, too, albeit, programmed to the lowest speed. This way, the solids to juice ratio can be controlled and ‘infused’ according to the material on hand. Cavalotto, irrefutably among the top five regional producers and responsible for the best wines that I tasted during the trip, is one such practitioner. Oak, too, is shifting. Barriques are largely a thing of the past, while the prevalence of traditional Slavonian botti is being challenged by the uptempo pervasiveness of Stockinger oak, from Austria.

Earlier Pruning

As flowering becomes more precocious with rising temperatures, spring frosts have become an even greater risk to the crop than otherwise. To lessen this risk, vintners are pruning later to delay the onset of fruit. Yet the vegetative and ripening cycles of the vine can only be regulated so much before its physiological tendencies become discombobulated and the fruit lesser quality. Shorter vegetative cycles and earlier flowering constitute an undeniable pattern that cannot, it would seem, be reversed.

As flowering becomes more precocious with rising temperatures, spring frosts have become an even greater risk to the crop than otherwise. To lessen this risk, vintners are pruning later to delay the onset of fruit. Yet the vegetative and ripening cycles of the vine can only be regulated so much before its physiological tendencies become discombobulated and the fruit lesser quality. Shorter vegetative cycles and earlier flowering constitute an undeniable pattern that cannot, it would seem, be reversed.

‘...the hottest thing since sliced bread.’

Timorasso

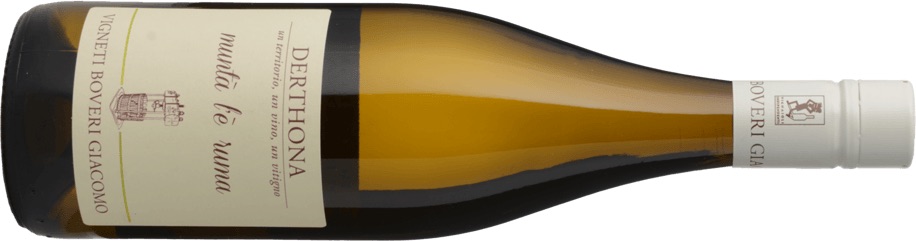

It seems that everyone is jumping on the bandwagon. The indigenous white variety of the Colli Tortonesi is the hottest thing since sliced bread.

Vigneti Boveri Giacomo Munta le Ruma Derthona Timorasso Colli Tortonesi 2018